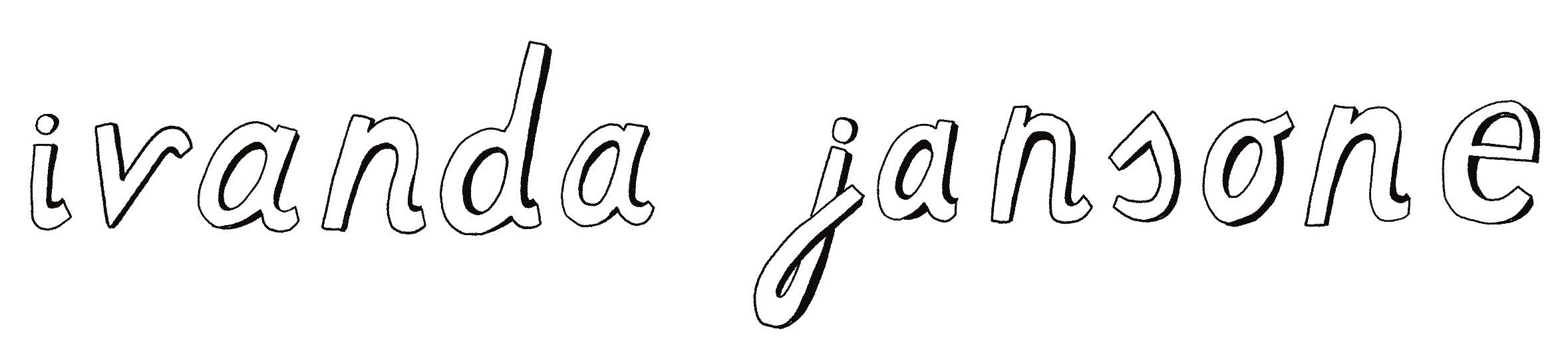

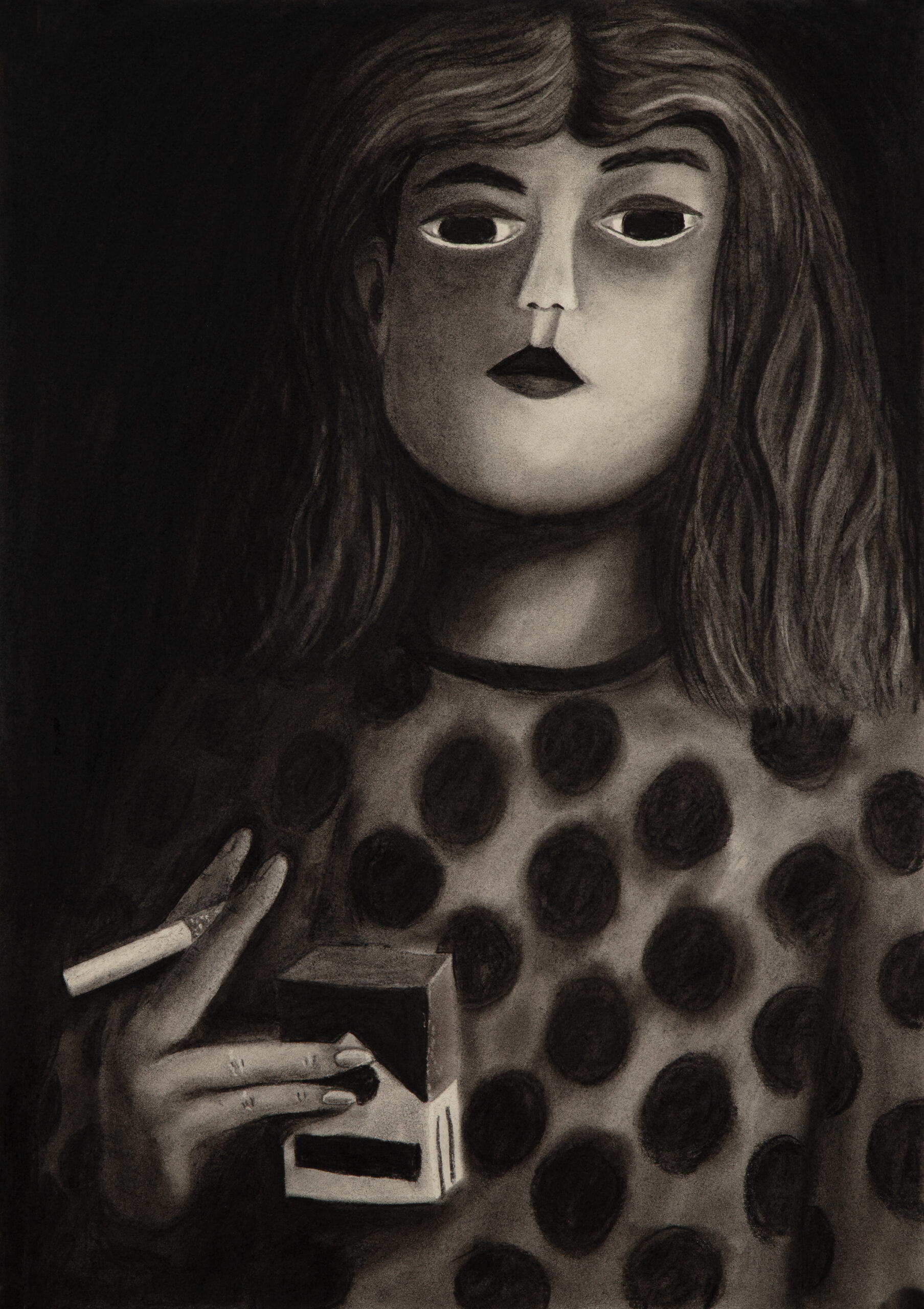

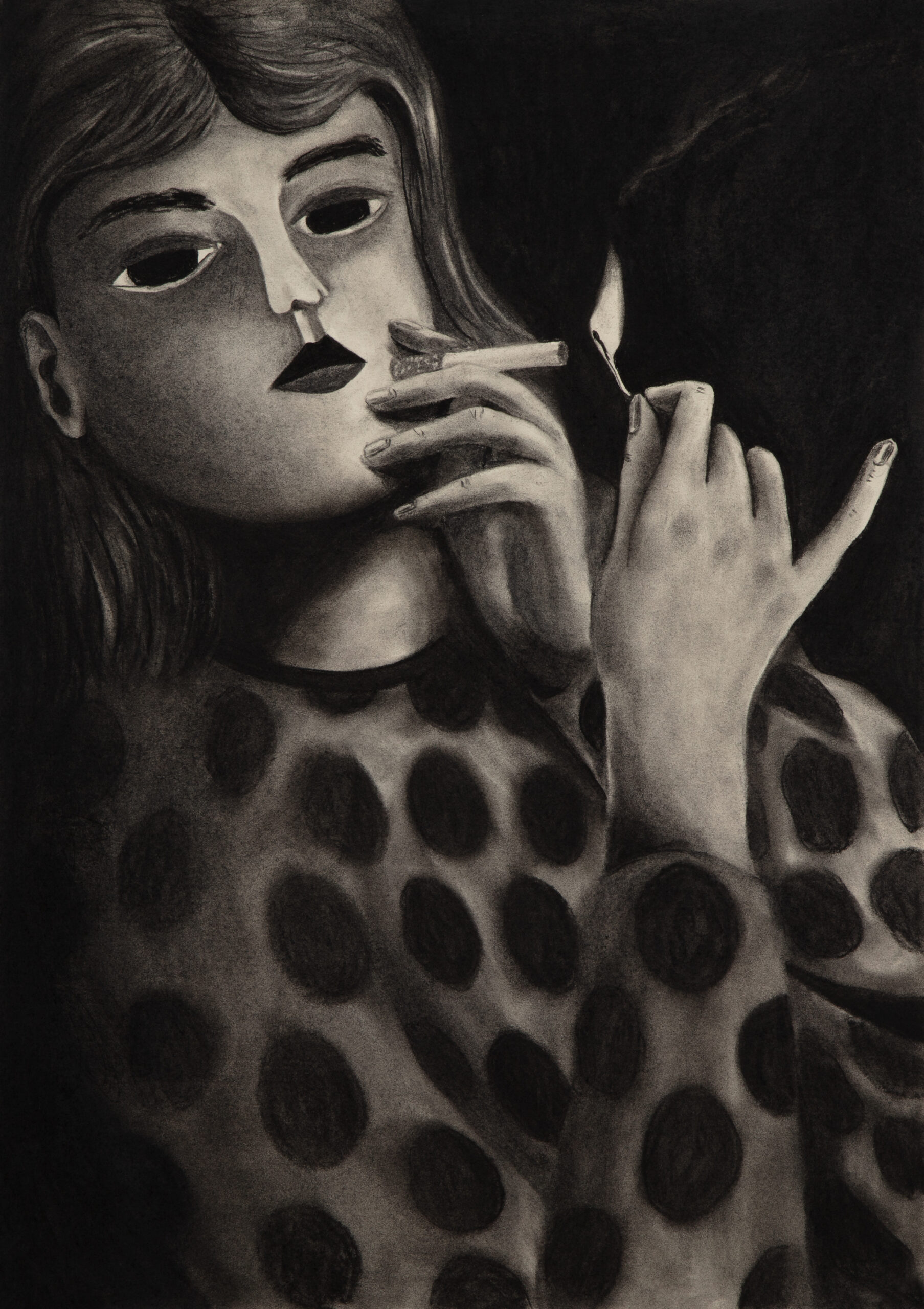

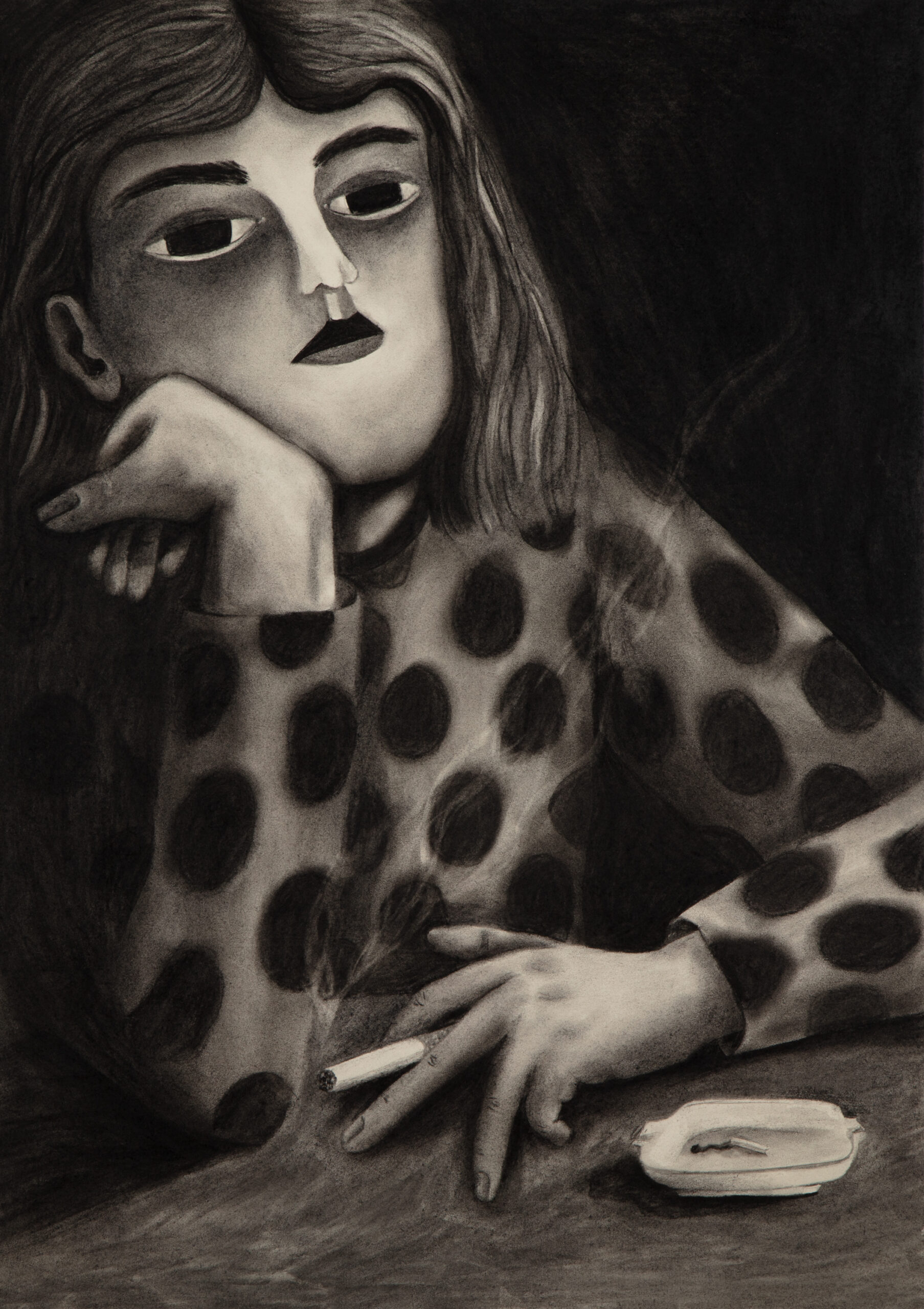

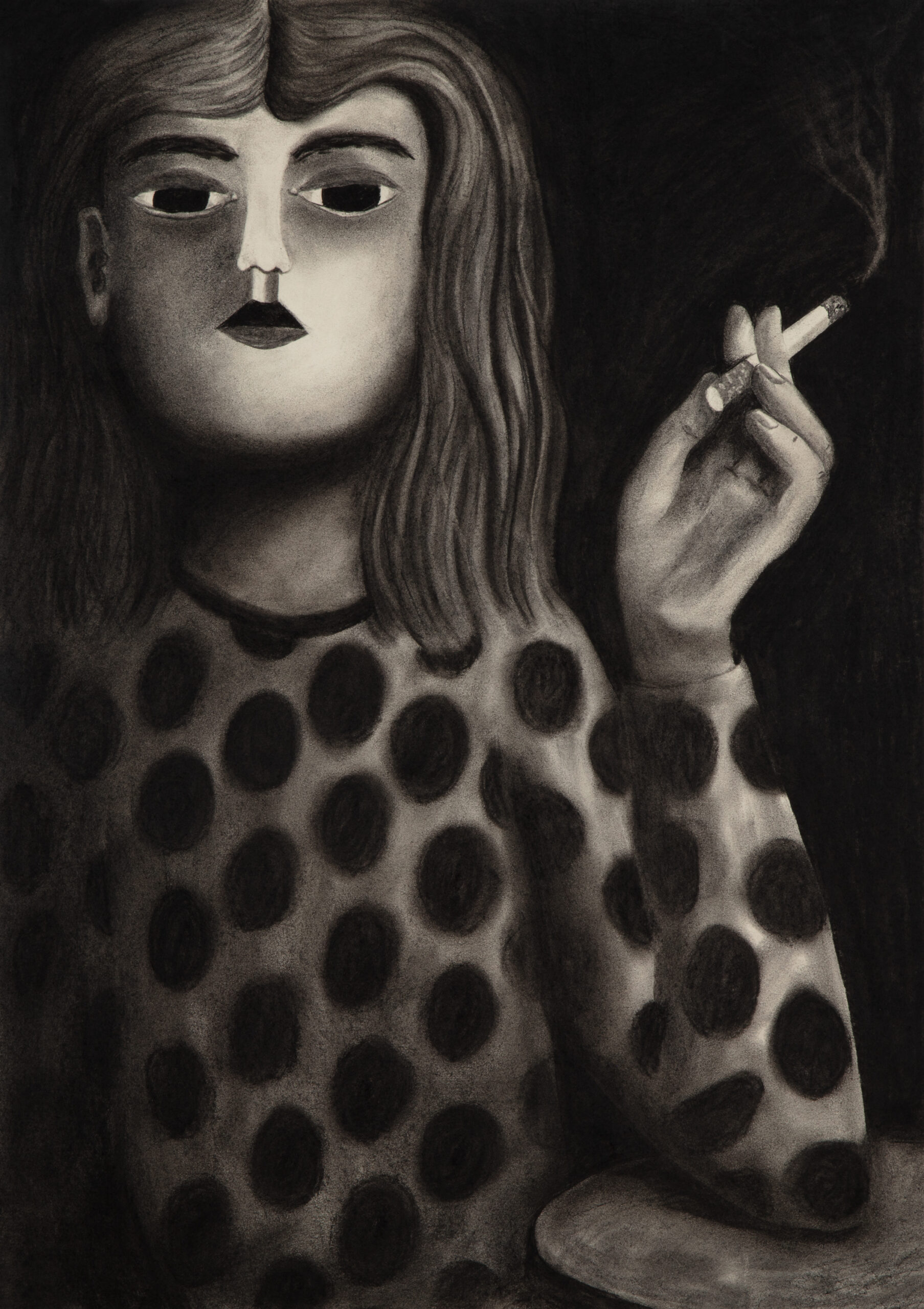

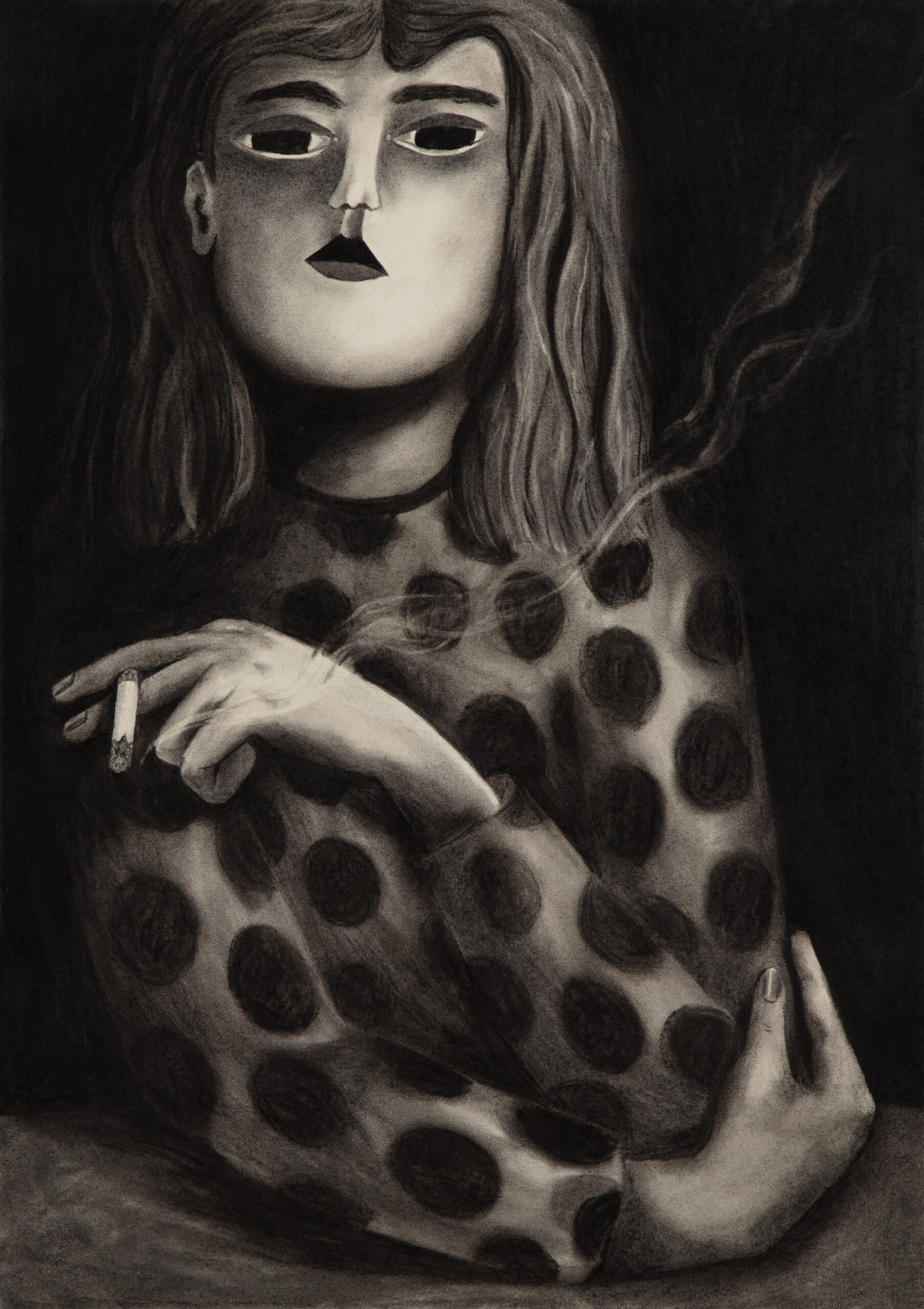

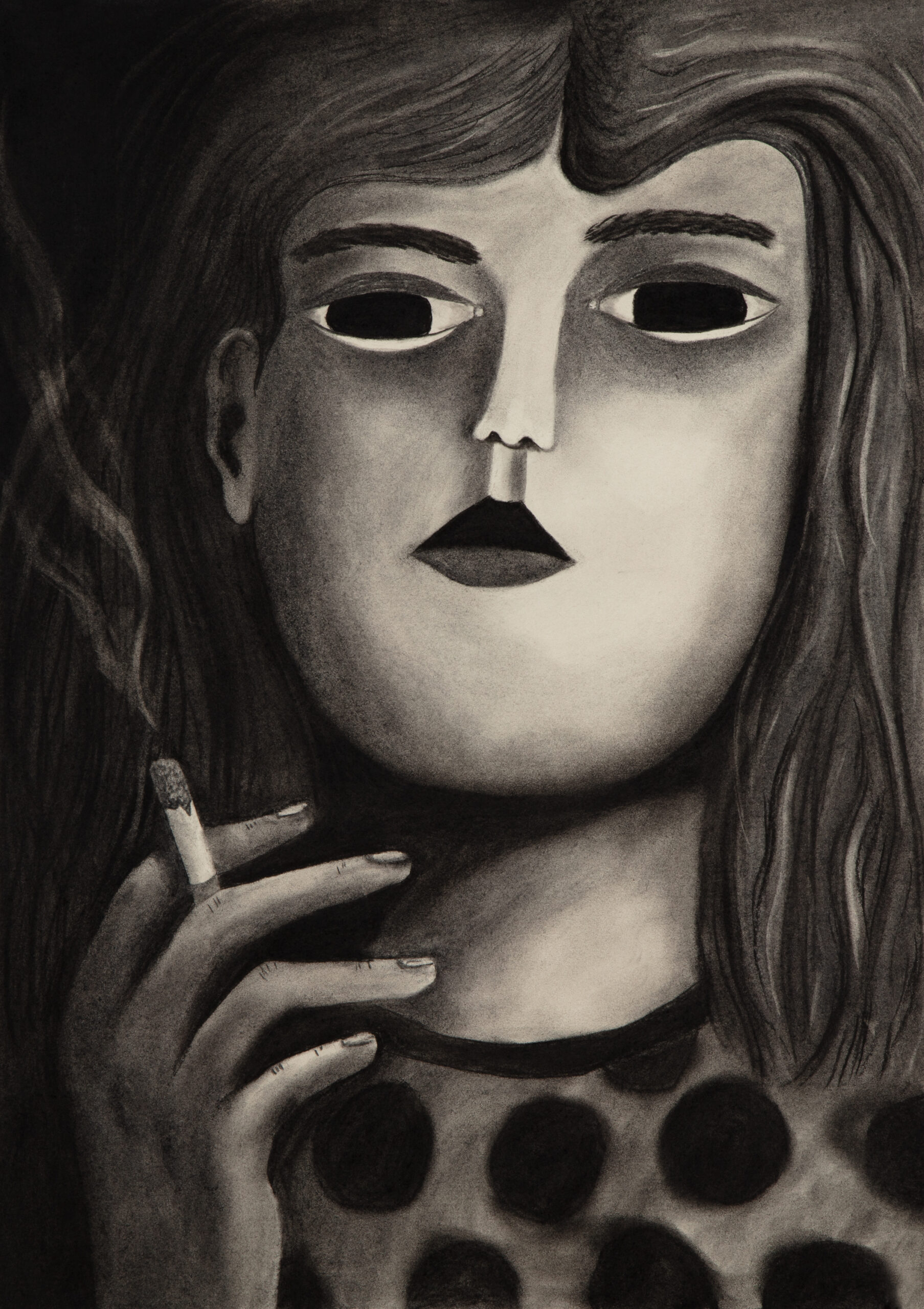

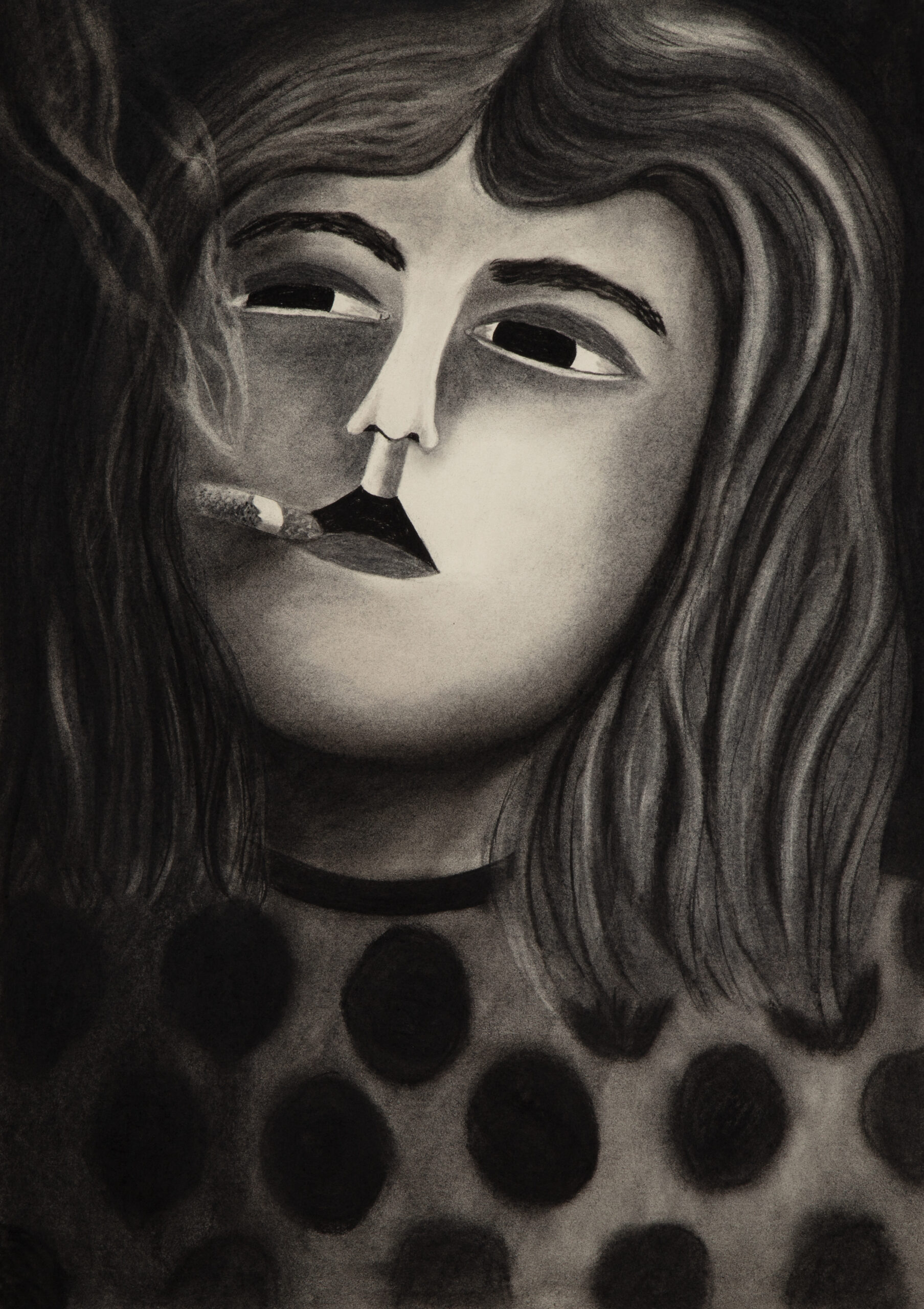

It is about a woman smoking a cigarette, but the story isn’t about smoking. Her pose is borrowed from art history, from the 19th century to today. Reference images, in order: Nan Goldin, Suzanne with Marlboro, 1980; Auguste Leveque, Portrait of Suzanne, 1866–1921; Édouard Manet, Plum Brandy, 1877; Alfred James Munnings, A Study of Miss Hancock, 1878–1959; Picasso, Young Woman Holding a Cigarette, 1901; Salvatore Fiume, A Susette, 1956; Fabio Hurtado, Travel Reading, 2010; Sarah Lucas, Fighting Fire with Fire, 1996.

There’s a clear pattern in the history of visual art: women are often shown holding cigarettes but rarely actually smoking them—especially in works made by male artists. It may seem minor, but it reveals a deeper cultural limit on women’s behavior and expression. In this series, however, the cigarette burns from frame to frame and becomes a quiet metronome, measuring time and quietly defying the constraints of traditional representation. The borrowed art-historical poses change their meaning once they’re placed inside a sequential narrative. The action happens between the frames. For me, showing a woman in the act of smoking means she takes back her space—active, not passive; embodied, not merely an aesthetic figure. This ties directly to the title: Restless Stillness. It’s contradictory, but it describes how I experience my role as a woman. This woman is a kind of self-portrait for me, a reflection of my own story. These structures are deeply rooted in culture and language, and they are not always easy to recognize as inequality. Art history, like history itself, has long celebrated men’s achievements—white, Western, authoritative. These are the names we’re taught and the stories we hear. In a way, I move within the same framework, but by changing the context I change the narrative.